In this review we are going to discuss what Popliteal Artery Entrapment Syndrome (PAES) is,...

Can marathon running improve knee damage of middle-aged adults?

In this review we are going to discuss the above paper which was released by L. Horga et al, in 2019.

Method:

The study took 115 asymptomatic novice runners aged between 25-73 who had registered for their first marathon. All volunteers underwent a knee MRI scan for both knees 2 months before a 4 month training programme for the marathon. They were then followed up 2 weeks following the marathon for repeat MRI scans of the knee to assess any changes pre and post marathon training and race. There were 31 drop outs from the training period due to injury and 1 person unable to complete the event on the day. Of the 83 who completed the marathon, 71 returned for their follow up MRI as did 11 of the dropouts during the training period. Therefore, the total number of pre and post MRI scans to be compared consisted of 82 runners. The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) was also used as a self-reported questionnaire with 70/82 participants completing questionnaire before and after the marathon.

Results:

- The study showed a significant difference in change in BMI pre and post marathon with the majority of marathon runners (67%) reduced their BMI as a result of the marathon training.

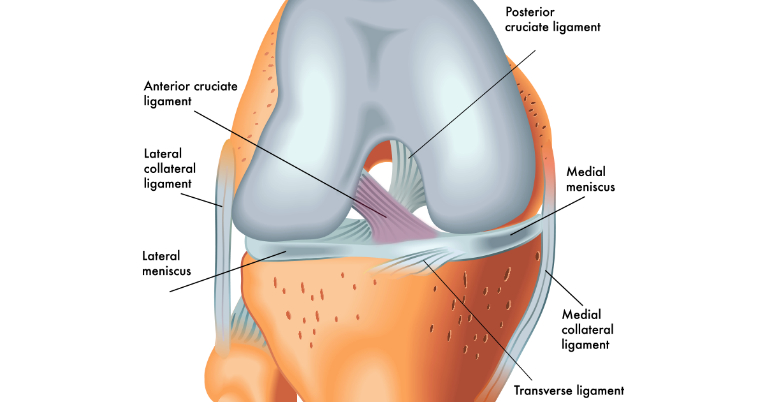

- No significant changes between pre-marathon and post-marathon KOOS scores were identified in runners

- 36% of participants had meniscal tears prior to the marathon and 16% had meniscal signal hyperintensity. After the marathon, only one runner showed an increased grade from a normal meniscus to horizontal tear in the left knee and overall no statistically significant differences were shown between meniscus lesions pre- and post-marathon. As of note, 83% of meniscal lesions were seen in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus and there was no significant differences in finishing times between people with or without meniscus tears.

- 65% of participants already had cartilage damage with 70% of those having lesions in the patellofemoral joint (PFJ). The patellofemoral joint was most affected after the marathon, especially the lateral patellar face

- 41% of participants who completed the marathon had subchondral bone marrow oedema (BME) prior to the marathon, with 54% of these lesions in the PFJ. However, improvement was noted in the medial compartment BME with 10 lesions improved in the tibia and nine lesions improved in the femur.

- Patella tendon, quadriceps tendon and semimembranosus tendons were the most common tendon related injuries prior to the marathon (42% of knees). 6 new insertional semimembranosus tendon injuries appeared following the marathon. Additionally, after the marathon, there was a significant increase in the number of knees with prepatellar bursitis (7 lesions) and ITBFS (15 lesions).

- 42% of marathon completing participants had ligamentous injuries, 90% with ACL lesions. However, following the run, there was only change noted in the collateral ligaments with 2 MCL injuries resolving and 2 LCL injuries occurring.

Discussion:

This information produced in this article can likely be critiqued in many ways.

Prior to the training programme and participation in the marathon, these volunteers were novice runners and sedentary individuals and were asymptomatic however 36% of them had meniscus tears and 65% had cartilage damage. Therefore, reinforcing current literature that shows that just because there are findings on scans, does not correlate to symptoms. Equally, following the marathon, there was no significant changes in the KOOS scores which is a self reported outcome measure looking at symptoms like pain and stiffness, completing tasks on a daily and higher level of function and also quality of life. Additionally, 10 subchondral oedema was improved in the medial compartment of the knee which may suggest that marathon running and/or training could have a protective effect on the knee joints of sedentary asymptomatic individuals.

However, with this study there obviously limitations. For example, the follow up MRI scan was at 2 weeks following the study so any long term conclusions cannot be made, as well as a small sample size meaning the results can not be generalisable. Participants also had no symptoms prior to the study therefore this would be difficult to put into practice however can still be useful in the educational aspect of treatment and management of conditions.

Unfortunately, there was no information provided regarding the training programme e.g volume, distance, frequency, intensity or periodisation in this study or in the supplementary material and there is no mention or record of any resistance training to supplement the marathon training. This potentially may have affected drop outs due to musculoskeletal injury and also post marathon MRI scans if there was further rehabilitation targeting prevention of injury to the the PFJ or hamstrings.

These findings challenge the stigma that running, in particular, long distance running has negative effects on the knee joint causing deterioration of articular cartilage and an increased risk factor for osteoarthritis. Obviously, these findings need to be taken on a case by case basis and individual screening would be recommended and appropriate education needs to be provided to the individual to prevent musculoskeletal injuries.