Exercise-induced leg pain (EILP) is an umbrella term to describe pain in the leg as a result of...

Differential diagnosis to calf strain: Popliteal Artery Entrapment Syndrome (PAES)

In this review we are going to discuss what Popliteal Artery Entrapment Syndrome (PAES) is, including the anatomy of the popliteal artery, classification of PAES, signs and symptoms, assessment and treatment options.

Even though this is the start of the blog I am going to summarise the what PAES is and allow you to read further if you would like additional information.

People who suffer with chronic lower limb pain e.g calf pain, especially athletes or recreational athletes can often have misdiagnosis. The calf complex which is made up of the gastrocnemius, soleus and plantaris muscle. Commonly acute muscle strain will result in an injury the medial head of the gastrocnemius due to sudden bursts of acceleration or increased eccentric overload. However, if muscular injuries are not managed appropriately then there is the risk of re-injury. However, it is important to be vigilant and be aware of alternative diagnosis such as PAES, especially if lower limb pain becomes chronic and it does not fit the normal signs and symptoms/criteria of a calf muscle strain.

PAES is caused by extrinsic compression of the popliteal artery, caused by the surrounding musculo-tendinous structures with the most frequent cause being the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle, which causes intermittent claudication. This may be congenital, or acquired through muscular hypertrophy. This often occurs in a young healthy, athletic cohort of people without cardiovascular risk factors, with a mean age of 32 years old. The important factor for PAES is that it results in exertional leg pain which therefore makes assessment and diagnostics challenging as often it is difficult to recreate the physiological demands of the symptoms. Symptoms are sudden in onset and relieve at rest. Patients will often have to stop during exercise as a result and often have pain in the feet and calves after exercise. Additionally, paresthesia, cramps, coldness, and blanching may occur, typically with an acute onset after exertion, however this is not the case in all. There is often a delay in diagnosis of up to 12 months and can often be misdiagnosed as Chronic exertional compartment syndrome. Management of the condition depends on the severity of symptoms as some patients may have mild symptoms only brought on with rigorous activity. However, in those more moderate-severe cases or people who require high intensity bouts of activity within their sport, surgical management is often warranted.

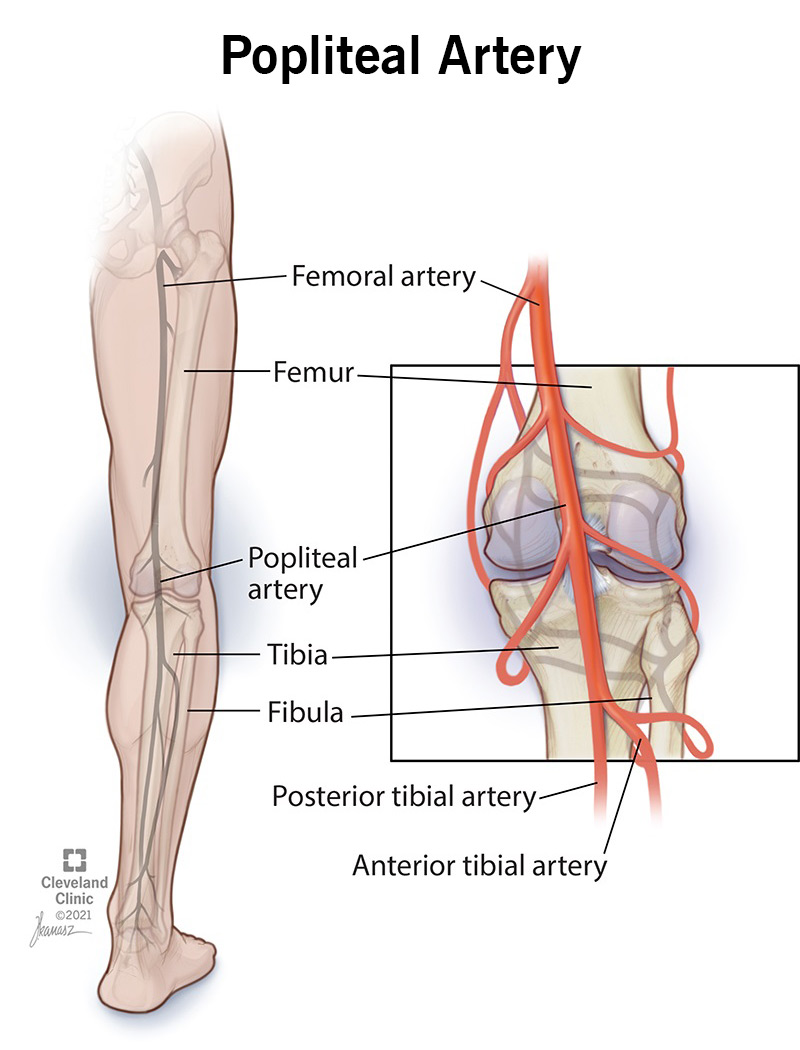

Normal course of the Popliteal Artery:

The normal course of the popliteal artery arises from the femoral artery as it passes through the adductor canal/hiatus into the popliteal fossa. The artery continues superficial to the popliteus muscle. It then continues into the deep part of the posterior compartment of the leg, passing under the tendinous arch between the two heads of the gastrocnemius and immediately bifurcates into the anterior and posterior tibial arteries.

Classification:

The below table shows a classification system to diagnose PAES:

| Type | |

| 1 | The popliteal artery passes medially and then deep to the normal medial head of gastrocnemius |

| 2 | The medial head of gastrocnemius inserts more laterally than usual. The popliteal artery descends normally but passes medially to the muscle |

| 3 | The medial head of gastrocnemius has an accessory slip arising more laterally that compresses the popliteal artery |

| 4 | The popliteal artery is compressed by running deep to the popliteus muscle or by an anomalous fibrous band. |

| 5 | Primary popliteal vein entrapment |

| 6 | Type VI Functional entrapment with no anatomical abnormality |

Signs and Symptoms:

Young, athletes with absent vascular risk factors - mean age is 32 years

High proportion of male athletes - 83%

Exertional leg pain, bilateral in 40% of cases

More acutely, patients present with arterial occlusion and limb-threatening ischaemia

Patients will present with pain, numbness, and cramping of the calf and lower extremity with exercise. Pain typically resolves with a few minutes of rest.

Assessment:

Lower limb arterial pulses are likely to be normal unless there is severe popliteal artery stenosis or occlusion.

Regarding bedside clinical tests, the ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI) may be within normal limits at rest. A fall in ABPI during plantar flexion or post-exertion is indicative of underlying vascular pathology.

Imaging:

A median of three diagnostic investigations has been reported as being required to reach a diagnosis:

1) Lower limb arterial angiography is the most common imaging modality utilised. Popliteal artery occlusion, compression and medial deviation can be appreciated and diagnosis may be aided when combined with provocation manoeuvres, e.g. ankle plantar flexion

2) Non-invasive duplex ultrasound (DUS) is commonly employed during initial investigation. Like angiography, popliteal artery compression may be elicited by provocation manoeuvres

3) Cross sectioning imaging - CT, MRI, angiography may be used to aid operative planning as it can be used to look at the underlying anatomy.

Why is it missed/why is diagnosis delayed?

The median delay before diagnosis of PAES has been reported as 12 months (range, 4 hours-120 months). However, there are reports of misdiagnosis and inappropriate management for up to 15 years. The diagnosis may be missed due to young patient age, often a lack of atherosclerotic risk factors, and difficultly in distinguishing from other causes of lower limb pain.

Consequences of delayed diagnosis can lead to arterial occlusion and critical limb ischaemia, post-stenotic dilatation or aneurysm formation (median prevalence 24% and 13.5% respectively), and potentially need for amputation.

Treatment:

1) Non-operative: Nonoperative management may occur with mild symptoms and with rigorous exercise only.

- This will include activity modification as well as observing/monitoring symptoms.

- Botulinum toxin A injections (Functional PAES)

- Similar to its use in chemically denervating the anterior scalene muscles to relieve neurovascular compression in thoracic outlet syndrome, botulinum toxin may relax the hypertrophied gastrocnemius to reduce PAES symptoms

- One to three injections of 100 MU (mouse units) of botulinum toxin into the medial head of the gastrocnemius and/or plantaris resulted in partial symptomatic improvement in 82.9% of cases. While the duration of action of botulinum toxin is only 3 to 6 months, the lack of any serious complications makes this a reasonable therapeutic trial for patients with functional PAES

2) Operative/surgical:

Early treatment is likely to consist of musculotendinous release of the popliteal artery, rather than a lower limb bypass which may be required once severe popliteal artery stenosis has occurred, with inferior outcomes.

Acute limb ischaemia requires urgent vascular intervention, whereas timely musculotendinous release of the popliteal artery has superior outcomes for symptoms resulting from intermittent occlusion.

- Aims of operative management:

- Decompress the offending musculotendinous structure

- Repair of vascular injury.

| Type | Surgery |

| 1 and 2 | Myotomy of the medial head of the gastrocnemius is performed, followed by rerouting of the popliteal artery |

| 3 | Resection of the accessory slip |

| 4 | Release of the popliteus, re-routing of the popliteal artery, with or without subsequent repair of the muscle |

| 5 | Release of the popliteus, re-routing of the popliteal artery, with or without subsequent repair of the muscle, with the additional decompression of the popliteal vein |

Outcomes for myotomy are excellent, with 1 and 5-year patency rates of 100%, respectively.

- Emergency treatment (indicated by Rutherford criteria):

- Rutherford Type I or IIa - Viable or marginally threatened extremities may be considered for elective surgery with or without CDT (Catheter-directed thrombolysis).

- Rutherford IIb - Immediately threatened limbs should undergo emergent revascularization

- CDT may be considered for patients with acute PAES with new, severe symptoms for less than 2 weeks (prior to clot organization) and angiographic evidence of acute arterial occlusion.

- Both fibrinolytic and mechanical thrombectomy approaches have been successfully reported.

- However, these techniques do not address the underlying anatomic pathology, resulting in high rates of re-stenosis.

- While the treatment for anatomic PAES is surgical decompression, management of the functional subtype may vary. Surgical approaches include lysis of fascial attachments, release of the plantaris tendon, and myotomy of the gastrocnemius, soleus, and/or plantaris. Recurrent or residual symptoms occurred in 9.2% of patients, with 7.1% undergoing a revision surgery.